'Me and Earl' and the Dying Identity

Posted Wednesday, July 8, 2015 at 4:22 PM Central

by John Couture

Films are largely a very personal experience. Traditional story structure usually follows one protagonist and his or her journey through the story. If this was a historical piece on film criticism, I would now talk about Gustav Freytag and his most profound contribution to dramatic structure, Freytag's Pyramid, but this isn't a historical piece of film criticism. In fact, it's barely film criticism at all opting instead to be thinly-veiled praise of an underrated film masquerading as something that it wishes it could be.

In many ways, this review/critique/love letter to Me and Earl and the Dying Girl follows the same arc as the Me in Me and Earl and the Dying Girl, Greg, the anonymous, privileged, white dude that serves as your guide through the film. Again, if this was a formal piece of film criticism or a thinly-veiled political manifesto, this would be the part where I take out my soapbox to rail against the oppressive white male majority. But, since my biology has predetermined my placement in said category, any soapboxing from me would sound flippant and glib. However, this does not prevent me from being supportive of more diversity in Hollywood (yes please), but that's a story for another day.

No, this piece doesn't contain a political agenda and no, you won't cry at the end of it. I promise. This is a story about a film that proves it can be as unconventional as it wants to be, yet still make an impression on its audience.

As someone who studied Psychology in school, I can't help but bring my experiences into a movie theater. You can scream suspension of disbelief all you want, but the reality is that every single person sitting in the audience brings this baggage into the theater. It is their identity. It's everything and nothing all at the same time. Identity is shaped by biology and environmental pressures and everything that we experience. Greg has carefully shaped his world so that he has no identity, and yet, he can't help that there are certain things beyond his control.

Greg is white, male and has been raised with a certain level of financial security that affords a school with the most amazing view of Pittsburgh that I'm pretty sure has ever been put on film before. As much as he tries to create the high school equivalent of Switzerland so as to avoid as much social conflict as possible, forces outside of his control introduce conflict in his world.

His world is turned upside down by the ultimate prime mover in any teen boy's life, his mother.

This is the part of the story where I tell you that there will be spoilers. You will ignore this warning because a.) you've already seen the film b.) the story is just too compelling to stop or c.) you realize that the film is called Me and Earl and the Dying Girl and that unless they are lying to you (and yes, they are), there will be more tears than laughs when it's all said and done. Fine, carry on, but you've been warned.

I've always been a huge fan of Connie Britton, but she has never been better than she is here as the typical mom who will do what it takes to make her child's life as unpleasant as possible. Of course, this doting is all under the guise of providing a safe and secure future for her child, but I think we can all relate to this scene.

Try as he might, Greg can not be neutral on this and his mom's nagging forces him out of his lifelong cocoon that he has created for himself. Greg has mistaken that cocoon for the ultimate survival identity to high school, but this single moment from his mom comes to define him more than any other thing that may have happened before the story started.

If this were a psychological treaty, this would be the part where I'd tiptoe into Freud's waters and re-introduce you to the Oedipus of your required reading list from high school or college.

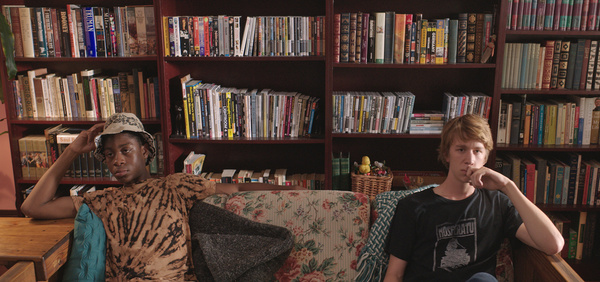

Like it or not, identity is not a mask that we can wear and change as it suits us. As Greg learns, trying to be everything to everyone results in him being an empty shell devoid of any real voice. He and Earl, who yes is a caricature but even as such he has more of an identity than Greg, make films but by their own admission "they're terrible." And Earl is right, they are terrible. The films themselves are hilarious and demonstrate Greg's true strength, but they also stunt his growth as a person.

By creating spoofs of other films, Greg is not forced to find a voice or connect with an audience, which is sort of the point of a film. The intended audience of his milieu is himself and Earl, which suits the two of them just fine. It's only after Rachel, the Dying Girl played to perfection by Olivia Cooke, discovers the film series that Greg is forced (again by another female in his life, his crush Madison) to consider the audience.

If this were a typical Hollywood film, this is the part where the protagonist steps out of his comfort zone and creates a masterpiece that cures the Dying Girl of her cancer and launches a lucrative career as a filmmaker. But this is anything but a typical Hollywood film.

This is an interesting place to talk about a device that has been getting a lot of traction in the last few years, the unreliable narrator. If this were indeed a historical piece on film criticism, I might invoke Wayne C. Booth and his groundbreaking tome The Rhetoric of Fiction.

This is the part where I spoil the film.

Greg is an unreliable narrator. And unlike the greatest unreliable narrators before him such as Keyser Soze and Tyler Durden, Greg isn't being unreliable to be devious on purpose. I truly believe that his lack of an identity is the main reason for his immaturity in telling his story. Right off the bat, he admits "I have no idea how to tell this story."

This is after the events of the film and after his supposed denouement and enlightenment, but yet he is still unable to be a reliable narrator because he understands that his unreliability is crucial to the telling of the story. Not once, but twice during the film, Greg reassures the audience that Rachel doesn't die at the end of the film despite titles that periodically remind you that this is a "doomed friendship."

I mean the film is called Me and Earl and the Dying Girl. Early on in the narrative he muses that his movies are so bad that his last one literally killed someone. In order for both his statements to be correct, someone else would have to die other than Rachel, but it becomes pretty clear that the supporting players aren't developed enough to serve any purpose in their death.

But Greg is savvy enough at the end of the film to realize that if he called his story Me and Earl and the Girl who Died After Watching My Film, then there would be no reason for the audience to invest in the story. Let's face it, Greg is not a very likable character despite his belief that by becoming the human embodiment of Switzerland, he's mastered the Kobayashi Maru that is high school.

Unbeknownst to himself, his lack of a true identity prevented him from being memorable and had he never befriended Rachel, no one would even remember who he was at his high school reunion. Only through his experience of letting someone get close to him was he able to grow to the point that he had something worthy to say, even if he had to fudge a few things along the way for dramatic purposes.

I could go on and on about this film, it really is that good and if you haven't seen it, then you should check it out soon before it disappears from your local multiplex. The story adapted by Jesse Andrews is on point and some of the bold choices made by young director Alfonso Gomez-Rejon are inspiring.

I must warn you though that if you're expecting explosions, the only loud sounds you will hear will be from the neighboring theaters playing the bombastic usual summer fare. No, Me and Earl and the Dying Girl is a quiet film that says so much in its intimate silences. Mostly, it says that no matter how carefully you live your life, you run risk of missing out on the hidden beauty that is just under the surface (or cover). So, dig a little deeper and you may even surprise yourself with what you find.